The news that the United Kingdom had been at war with Germany in 1914 had stirred a rather similar response here in Victoria to that in England in 1852 with the arrival of news that gold had been discovered here in Victoria awaiting those prepared to set sail and dig for it; those responding to the call earning the tag of ‘Digger’. This latest flow, however, had been in the opposite direction and been responded to by the sons of those same diggers returning to defend the motherland from an enemy intent upon destroying it! No call this time for passage money, the Army would see to that and each respondent would be issued a gun and uniform to cheer them on their way.

Across Victoria, they’d enlisted in their thousands. Throughout Australia, some 412,000 young men had responded to the call with few among them ever remotely aware of what might lie ahead of them. All of them the sons and grandsons of those who’d come to speak of England as home who’d enlisted with their family’s blessing! England was under attack and must be defended at all costs. Within the then Shire of Eltham some 400 had responded to the call!

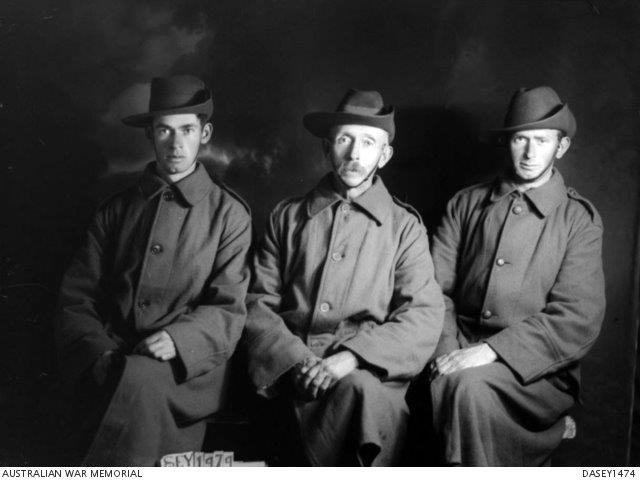

Amongst them, had been three members of the Harris family: William Shelley Harris and his two young nephews, Robert Jubilee and Charlie with Robert never to return, the other two returning home broken men — their names now all but forgotten! Today, a hundred years after their great adventure is therefore an appropriate time for them to be recalled from the shadows to be celebrated as the real flesh-and-blood Diggers they’d proven themselves to be.

The Harris saga had begun back in England soon after news of gold being discovered in this then remote corner of the vast British Empire. News that had seen Victoria’s population grow seven-fold within the decade. Amongst the first to arrive had been Robert Joseph Harris, a young man of positive means and a tenuous connection with the novelist, Charles Dickens, and an even closer one to the reformist Caroline Chisholm and her Family Colonisation Loan Society. Robert’s association with the Chisholms being that his role on board the SS Athenia when it had sailed from London in September 1852 had been to oversee the well-being of the scores of single women whom Caroline had gathered around her, intent upon securing them a better life in Victoria away from the vice-ridden streets of industrial London.

Very little is known of Robert’s first year in Victoria other than that, he’d married Elizabeth Hibbert in Melbourne in 1854 and by 1860 had settled in St Andrews, where he’d opened a large room in his home as Common School No 128, later to become today’s State School No 128, with himself as head-master. Over succeeding years, Robert had served in a similar capacity in the first Watson Creek, the first Christmas Hills and finally the first Panton Hill State School during which time his St Andrew’s home had become locally known as the ‘Harris Assembly Hall’.[1]

Panton Hill had been where his son William Shelley Harris, the first of the soldiers in this study had been born and grown up to become the proud Australian he’d later prove himself to be — the home within which his other son, Robert Charles Harris, the father of the two other soldiers in this study had been born and lived out his formative years.

Let’s first take Robert Charles Harris, the eldest son of the pioneer who, having received his education at the Panton Hill State School to Merit Standard, had in 1873 been apprenticed to the Evelyn Observer, the county newspaper, published weekly in Kangaroo Ground — a paper which he’d later own and edit for an additional fifty years.

This brings us to his two other sons, Robert and Charles who’d been amongst the 400 from the Shire of Eltham who’d donned uniform and marched off to war in 1916. Here, our best clue to the family’s world-view is Robert, the eldest whose second name ‘Jubilee’ had been bestowed upon him because he’d been born in the 50th year of Queen Victoria’s reign.

Some little time after his father’s rise to the editorship of the Evelyn Observer, young Robert Jubilee (widely known as ‘Bob’), had been apprenticed under his father as a printer on the Observer staff. Regardless, his sporting loyalty had remained with Panton Hill where he’d soon after become captain of the local football team.[2] As a promising all-rounder, he’d also represented Panton Hill in cricket and had batted for it that proud day when the club had played the Melbourne Cricket Club on the MCG. Amongst Robert Jubilee’s other pursuits had been playing competitive tennis for the local ‘Summer Hill’ Tennis Club and attending vestry services of a Sunday in St Matthews Church, Panton Hill. Already a man with the world at his feet, he’d then marched off to war with thousands of other Diggers never to return to his old stamping grounds in the green Yarra Valley.[3]

A prime motivation in both Harris brothers’ growing up years had been the frequent letters dispatched back home to the Evelyn Observer by their uncle, Corporal Shelley Harris, who’d enlisted in the Bushmen’s Corps in the Boer War — letters that had regularly appeared on young Bob’s Evelyn Observer desk for him to type-set into the next issue of his father’s county newspaper!

Everyone had thought the world of Shelley Harris who’d spent much of his early years up in the Kinglake Ranges fossicking for gold in the years following the short-lived ‘Mountain Rush’. Shelley had been the wild one of the scholarly Harris family who, like ‘Banjo’ Paterson’s ‘Clancy of the Overflow’ had built himself close affinities with the wild rugged ranges!

It had been through Shelly’s letters back home to his brother, the newspaperman, that the readers of the Observer had kept in touch with the Boer War as it had unfolded after 1899; letters vividly interpreting the campaign as being part of a wonderful adventure into a world of fighting men unwavering in their dedication to crush all who dared threaten the Empire. Throughout the early months of 1900, the Harris boys had proudly followed Shelly and his horse across the hot African veldt on long marches that would end with the inevitable skirmish and predictable victory against the despised Boers.

By July 1900, Shelly and his Bushmen’s Corps had been under siege at Mafeking[4] encircled by 8,000 Boers sporadically shelling the town with their powerful ‘Big Ben’ field gun. Shelly’s letters tell of how it had taken seventeen seconds for the shells of ‘Big Ben’ to reach Mafeking, and of how their commander, General Baden Powell, had very sensibly set up a bell in the centre of town to warn all and sundry that they’d exactly that extent of time to reach a bunker. After 217 tedious days, the siege of Mafeking had been broken with the arrival of reinforcements under Lord Roberts.[5]

Later, Shelly had moved on to the Elands River where, isolated upon a kopje for thirteen days, his 500 strong garrison had been besieged by 3,000 Boers before reinforcements had arrived to relieve them.

Throughout the war, the enemy is seen to be using guerrilla tactics with the British eventually forced to act accordingly by destroying farmhouses, confiscating stock, burning crops and imprisoning Boer families behind barbed wire. Like all wars it had been a cruel war and, like all others, it had finally drawn to a close and allowed Shelly to return home to the Yarra Valley with the thrill of it all still coursing through his veins to an extent that fourteen years later at the age 47, he’d enlist in WW I to again defend the Empire! Later, pensioned off because of his age, he’d been appointed Ranger at Jehoshaphat State Park, where his exploits live on in the name ‘Shelly Walk’, a tribute to a genuine ‘bushman of the old brigade’ who in his later years would think nothing of trudging all the way from Kinglake to his brother’s, home in Panton Hill, then back again the following morning to disappear into his beloved hills

Thus the Harris family of Panton Hill can be said to have stood at the centre of any understanding of war as it had played out locally until 1914. As with most other settler families of Shelly’s day, the Harris family had had its beliefs deeply rooted in English soil and had been proud supporters of the Empire and everything it had stood for in their day.

Shelly’s nephew, Robert Jubilee (‘Bob’) Harris, had enlisted for WWI in what has been described as `a spur of the moment affair’ which had seen his younger brother, Charlie soon follow in what both had seen as a wonderful opportunity to prove themselves in battle and visit a world that might otherwise be denied them because of Australia’s then remoteness. At first, their letters back home had come to the Evelyn Observer from ‘Bob’ the budding journalist who’d written of how, having completed his basic training at Seymour and Broadmeadows, he and his mates had received rousing cheers from every railway station along the way to Port Melbourne where in August 1915 his 3rd Reinforcement of the 24th Battalion had been drafted aboard the SS Anchives within which, he and his mates had slept packed like sardines in a tin, 200 to a cabin, all the way to Egypt.[6]

Upon his arrival in Egypt, ‘Bob’ had undergone further training with sporadic leave into what he’d seen as a colourful yet crime-ridden Cairo, before being trans-shipped across the Mediterranean to arrive on Anzac Cove on 13 October some six months after the first ANZAC Landing on 25 April 1915, with thousands of young Australians already either dead or wounded! Few opportunities here for the brothers to prove themselves in battle, the ‘daring do’ glory days of the landing having long been over. They’d instead found themselves pinned down by Turkish mortars and machine-gun fire for months on end in grim, disease-ridden trenches and dugouts wherein life had been the lottery of who’d be hit and killed and who’d be left to stretcher the dead back for burial behind the lines.

‘Bob’s letters — perfectly couched in journalese for the readers of following editions of the Observer to follow — speak volubly of mateship and how he and his comrades each had the name of their home-town on their caps: ‘I have Kangaroo Ground on mine and have received no little barrack in the trenches over the name!’[7] Mostly though, it had been a matter of knuckling down and surviving the hazards of weather in open trenches performing the most menial of everyday tasks surrounded by shell-fire and disease. Bob’s letters back home contain the names of many another `district chap’, identified by his cap name. Amongst them, Oscar Walters, Percy Glennon, William Apted and Arthur Howard of Panton Hill; a soldier by the name of Gell from Yarra Glen, T. Huntley, Clive Stewart, W. Hill, Dowdsdell and Pollard from Diamond Creek, Black and Commerford from Lilydale, Corporals Pratt, Wallen and Morris of Watsons Creek; Love from Warrandyte, Maskell and Meadows from Research: ‘the other week I was talking to a chap of the 23rd who knew the Johnstons of ‘Pretty Hill’, Kangaroo Ground, and an old Diamond Creek boy who’d gone to school with Jack Ryan. By November that year, ‘Bob’ Harris had been able to write back home to say that he’d at last experienced a taste of the privations of war with the battlefield around him covered in snow, shells exploding and Turkish machine-gun fire picking off the men around him.

With the Turkish front now at stalemate, these Anzacs had eventually been ordered to evacuate and remobilise for war on the Western Front. ‘Bob’s letters along the way describe the evacuation and the voyage westward to Marseilles and the train journey north across the beautiful French countryside with its glorious panoramas of vineyards and orchards and women bringing in the harvest which he sees as reminiscent of Kangaroo Ground — regretting the fact that he’d miss so much of it due to his train rumbling on through the night. By July, nearing the front, he’s in a contemplative mood, very aware of what might lay ahead of him:

‘I am once more on the eve of going into the firing line … the land here is a regular garden, excellent crops growing right up to the firing line, and the women and children live on just the same as in peace-time. I’m in good spirits considering what I have to face … you can read between the lines. The next fortnight will tell the tale, and the next few days will be very dangerous, so — goodbye.[8]

That is the last ever heard of Robert Jubilee Harris! The following day like thousands of others in the prime of life, he’d been killed in the Battle of Fromelles, described as being ‘one of the bloodiest and most futile of 1916’; the very worst night in Australian Military History with 5,533 5th Division Australians Dead — amongst them Robert Jubilee Harris — a young man with huge potential destined never to see the green rolling hills of Kangaroo Ground again. His last letter had been dispatched on the night prior to the battle.

Within a fortnight his family had been informed; his father never fully recovering from the shock loss of his proud, high achieving son! Robert’s pen had been taken up by his brother Charlie who, in graphic detail had written of the horror of it all in a battle which had led to Robert’s death and left him wounded.

‘I consider myself very lucky. The line we held was chopped to pieces and I was one of the few who came out alive and sound. Talk about a living hell; it was awful. I was buried twice but not so bad that I couldn’t get free; knocked over once with concussion, struck on the back with a piece of shrapnel. I will not attempt to describe the ghastly sight at dawn, but only say that the terrific fire had unearthed dead Germans and laid them side by side with our own poor fellows.’[9]

Despite his injuries, Charlie had soon after been dispatched back into the trenches — this time at Ypres where he’d again been wounded. His next letter had come from Bradford War Hospital in Yorkshire after the Battle:

Ypres is a rum looking place and no mistake; nothing but a mass of ruins, and the renowned Hill 60 is nothing but a bare ridge … my word those mines are some class by the craters they leave … some of us machine gunners were holding a secret position. Well, this position of ours was not altogether a pleasant home as all sorts of missiles were flying about.[10]

Charlie Harris had barely survived Ypres and had been again shipped back across the Channel to recover from his wounds after which he’d again been dispatched to the Front — this time by way of the troop-ship, ‘Barunga’. Luckily for him he’d never made it back to the front! The ‘Barunga’ had been torpedoed in the English Channel and Charlie who couldn’t swim had been plucked from the water and been eventually repatriated back to Kangaroo Ground.

It had been Charlie Harris who, after the war, had been appointed caretaker of the Memorial Tower in Kangaroo Ground where he’d later plant the Cypress trees that surround it today. Later, when he’d recovered sufficiently from his wounds, he’d become an orchardist along the Panton Hill Road and like many another who’d tried their hand at orcharding in the post-war years, he’d found it, too, a battle for survival with depression year prices seldom meeting the cost of production.[11]

Somewhat disheartened, but still not defeated, Charlie’s passion (or necessity), had become rabbiting, and fishing for cod in the Yarra. Armed with yabbies caught in local dams he, and his mates Ted Lacey and George Peters, are said to have enjoyed nothing better than to spend their evenings camped along the Yarra[12] tending their night-lines, yarning their time away around their night-fire. One imagines this had provided Charlie ample time to relive the old camaraderie of the Battle of Ypres, and the horror of the Battle of Fromelles and to wonder why it had been that those who hadn’t returned had been so quickly forgotten on the home-front.

A Roll of Honour containing the names of those who’d enlisted from Evelyn County had appeared in the Evelyn Observer of 4 August 1916. Arranged under the banner of their home districts, those listed under Kangaroo Ground had been: Frederick Barrett, Charles Harris, Ralph Moore, John Bell, Robert J. Harris, Albert E. Morris, Roger Bell, Robert Irish, Albert Morris, W. Bromage, Alfred Johnston, Thomas Scarce, Gordon Cameron, Leslie Johnston, John Walker, E.P. Cameron, John Kennedy, William Wippell, William Dawson, William Longstaff, Frank Gower and J.W. Mackay — 22 names. By war’s end — a fuller list of 56 of those from the Shire of Eltham who’d fallen had been compiled and emblazoned in bronze above the portal of the Kangaroo Ground War Memorial Honour Roll.[13]

Mick Woiwod June 2016

[1] Mick Woiwod, Kangaroo Ground: The Highland Taken, Tarcoola Press, 1994; Conversation with R.C. Harris’s nephew, George Taylor, 12 October 1993.

[2] Known as the Dahlias.

[3] Harris file in the Andrew Ross Museum, Kangaroo Ground.

[4] Conversation with Harris descendent, George Taylor, 2004.

[5] ‘Those who went off to War’ in Kangaroo Ground: The Highland Taken, p. 241.

[6] Evelyn Observer,

[7] ‘Those who went off to War’, Kangaroo Ground: The Highland Taken,

[8] Evelyn Observer 17 July 1916.

[9] Pte C.T. Harris 10 August 1916, Evelyn Observer (no date).

[10] Pte Harris, Evelyn Observer.

[11] Kangaroo Ground Memorial Tower notes & conversation with George Taylor 1993.

[12] The Harris family seem to have all been keen anglers. The Evelyn Observer of 2 November 1882, records that J.S. Harris that year had caught seven or eight codfish in the Yarra weighing between seven and twenty-two pounds.

[13] Harry Gilham, Kangaroo Ground War Memorial Advisory Committee Notes.

Photo: Australian War Memorial

This story was first published in “Fine Spirit and Pluck: World War One Stories from Banyule, Nillumbik and Whittlesea” published by Yarra Plenty Regional Library, August 2016