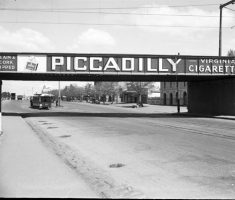

In 1928, increasing delays to traffic traveling to and from the city to Northcote and Preston and points further north via Queen’s Parade and High Street were alleviated when the level crossing just on the south side of the Merri Creek was replaced by an overhead railway bridge (pictured below).

The original plan was for a steel bridge to extend from Clifton Hill station over Queen’s Parade, but this was abandoned at the instigation of the Collingwood Council’s engineer Mr. W. E. Thompson who suggested packed earth embankments on either side linked by a shorter steel structure across the roadway was a much cheaper and quicker alternative. Construction of the overpass also allowed the Melbourne to Clifton Hill and the Northcote cable trams to be linked after with some difficulty; although the cables traction was compatible, it was discovered that the newer Northcote trenches had been excavated to a lower depth – ultimately, however, the result was Melbourne’s longest cable route until trams were replaced by double-decker buses in 1940

Unfortunately no such relief was available for those heading to Heidelberg and surrounds via Heidelberg Road, then the only access from south of the Merri Creek.

Their problems were multiplied as the level crossing immediately north of the station carried both the Preston-Reservoir and Heidelberg-Hustrbridge lines, plus occasional services on the original link from Clifton Hill to Spencer Street via North Fitzroy, North Carlton and Royal Park. Complaints over extensive delays were numerous, but let us quote The Herald of 31 January, 1930 …

“A visitor from a really modern city would be astonished to find in Melbourne a sight which may be witnessed any evening from about half-past five to six o’clock at the Clifton Hill crossing on the Heidelberg Road. This is what happens – the gates clang shut at 5.36, when the train from Melbourne to Heidelberg slides into the station. A couple of hopeful motorists have drawn up for what they confidently expect will be half a minute. Out goes the 5.36, but the gates remain closed for the 5.37 up train from Heidelberg. There are three lines running out from Clifton Hill, to Preston and Reservoir, to North Carlton and North Fitzroy, and to Heidelberg, Eltham and Hurstbridge. The 5.37 hurtles by and motorists start up their engines, but the gates stay closed, for at 5.39 the Reservoir train comes from Melbourne. It departs, and the signalman whistles quietly to himself. It is no use opening the gates, for the 5.42 is due in a couple of minutes, and the line of motors is lengthening. No use irritating those who cannot get through on the first “wave”, he thinks. The 5.42 comes and goes, and the 5.45 from town. At the same time the 5.46 from Preston and points northward comes in, and then the 5.48 down train, followed by the 5.51 down and up (you can back them both ways at Clifton Hill). The horns honk like wild geese in a temper, but the signalman waits for the 5.53 up train. It goes up and the spirits of home-returning drivers rise accordingly. Now let’s go! No, wait a bit. Here comes the 5.54 down train. Hardly has it passed when a train from North Carlton sneaks in the other way. Now! The horns get insulting; the line of cars extends even further, but the 5.57 from town must get through, it comes; it goes, and at long last the gates swing open. The signalman grins, and the long lines of cars slowly disintegrates …”

A survey conducted in 1933 by Heidelberg Council on a weekday between the hours of 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. revealed that the gates at the crossing – which were controlled by an operator from a signal box – were closed 187 times for a total of just over five of the twelve hours with often up to four trains passing without vehicles being allowed to move; traffic backed up for over 300 yards for up to eight minutes and drivers having to stop three times before clearing the crossing.

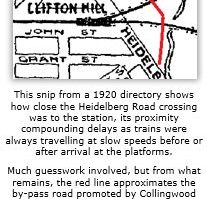

An accepted rule-of-thumb at the time was that a minute lost in traffic delays cost the community a penny, and on that basis, between £9,000 and £10,000 was being lost by industry and the community generally annually. The delays were exacerbated by the proximity of the crossing to the station, meaning that trains were travelling at slow speed as they entered or left the platforms.

Just after the completion of the Queen’s Parade bridge in 1928, a proposal was put forward by the Railways Department that the crossing be replaced by either lowering Heidelberg Road or providing an overhead bridge at a cost of £77,000, of which Heidelberg was to pay £23,000 and Collingwood £25,000, but the with worsening economic crisis on the brink of the Great Depression, both municipalities declared the cost out of the question.

Thompson however again put forward an alternative solution, one which Collingwood continued to favour for nearly twenty years – a bypass off Heidelberg Road east of the crossing emerging in Queen’s Parade, the crossing replaced by a short bridge over the Heidelberg track and a subway under the embankment of the new Preston-Reservoir line bridge, The cost of this was put at £14,000, increased subsequently to £18,000 when a later alternative included bridges over both railway lines.

Although there were no fatalities recorded at the heavily-controlled crossing, there were safety concerns over having traffic backed up at the gates for hundreds of yards, and then released in a rush, causing an unbroken stream of frustrated drivers racing along Heidelberg Road trying to make up lost time and creating a menace to pedestrians and the potential for disastrous multiple-car pile-ups.

A number of inquiries throughout the early thirties – unfortunately during the Great Depression when few funds were available for infrastructure improvements – identified Clifton Hill as the second highest priority in plans to abolish the four worst crossings; Melbourne Road, Newport the highest, the other major bottle-necks in Paisley Street, Footscray; and Glenhuntly Road, Elsternwick. By 1937, the cost of replacing the crossings was estimated at £274,000, that specifically of Clifton Hill £73,000 for a subway or around £50,000 for an overhead structure, although the Country Roads Board later came up with an alternative bridge plan at £27,258.

The Railways Commission Mr. H. W. Clapp voiced his personal opinion in favour of the subway option, suggesting that although more expensive, “this approach was always to be preferred in a modern city”. Although unstated at the inquiry, other sources suggest a subway was preferable both visually and given the unknown of compensation that may be payable to shop and house owners impacted by the potentially large overhead structure.

Equally detrimental to motorist’s hopes was that Heidelberg and Collingwood still could not agree on the approach – subway or bridge versus a bypass road. Heidelberg supported the subway plan but declined to say whether the Council would contribute to the cost or bear a share of the interest charges, pointing out they felt that as three hospitals and a public institution were included within their boundaries the question was “more of national importance than municipal.

For its part, the Railways Department suggested that it was running at an annual deficit of around £500,000 and the only way the removal projects could proceed was through Federal Government funds which it was hoped might be made available as part of the “sustenance” work programs created to relieve the problem of the unemployed during the Depression, but nothing was forthcoming.

The Country Roads Board for its part ruled out the bypass road proposal, calculating that with an estimated 8,000 vehicles using the alternative daily, an additional 420 miles of travel would be required which at current estimates would cost the community around £6,700 per annum, rapidly diminishing any “up-front” savings. (Based on their calculation, the bypass would have been a little over a half-mile in length).

Any prospects of an early resolution came to an abrupt halt with the declaration of the Second World War in September, 1939.

Following a virtual shutdown of capital expenditure during the conflict, the Railways Department announced in October, 1945 a highly ambitious expansion program involving £15 million over the next ten years planned to overtake the arrears in track works and rolling stock, and to undertake several big construction projects delayed by the conflict including £400,000 for removal of the four level crossings. This expenditure was to be carried out concurrently with Victoria’s share in the national gauge unification scheme, the conversion of Victorian lines to standard gauge estimated to cost a total £21,500,000.

Regardless of the pounds, shillings and pence that might have been involved, this and other similar programs had to wait as a chronic shortage of construction materials severely restricted infrastructure, commercial and domestic building for several years, even at one stage threatening the preparation of some sites required for Melbourne’s 1956 Olympics after its successful bid in 1948.

The Clifton Hill overpass project finally started to take real shape in July, 1954 when the State Government revived proposals to abolish the “most dangerous and time-wasting” level crossings in the metropolitan area now at cost of £1,540,000. The level crossing in Heidelberg Road was at the head of priorities – the Footscray, Elsternwick and Newport crossings joined by another in Nepean Highway, Moorabbin, the latter included with the growth of the southern beachside suburbs in the intervening period.

Given the Heidelberg roadway sloped away from the crossing for about a quarter-mile on either side and with the Merri Creek offering a natural drainage outlet, most expected that the earlier proposal of diverting the road via an underpass beneath the railway line presented the most viable – although still most expensive – option, but test boring revealed a solid layer of volcanic rock just below the surface, a phenomenon previously encountered a number of times across the creek in South Northcote and believed as a result of Rucker’s Hill ancient origins as an active volcano.

Surveys also revealed that about 40 percent of the traffic using Heidelberg Road to the east of the crossings turned out of, or into, Hoddle Street, hence it was confirmed in December, 1954 that an overpass would be required and in May of the following year, plans were in place for a structure with four traffic lanes – two in either direction separated by a four-foot median strip – but with provision to expand to six if required.

The total cost was estimated as £422,000 and to reduce disruption to both rail and road traffic, the Country Roads Board undertook the manufacture of precast concrete structural components prior to tenders for construction being issued.

These tenders were ultimately issued on 10 December for a structure 262 feet long varying in roadway width from 72 to 84 feet, consisting of 11 reinforced concrete beams; two pedestrian subways each eight feet wide and 70 and 143 feet in length respectively; the construction of 1,313 feet of road approaches comprising ramps, embankments and retaining walls, and finally, the reconstruction and widening of 1,200 feet of roadway.

Despite some disruption during a dispute between the Master Builders Association and various building unions (which also impacted the preparation of some sites under construction for the 1956 Olympics), the overpass opened in May, 1957, for some months an attraction for Melbourne motorists wishing to try out the steep and sharply curves presented by the on and off ramps somewhat reminiscent of the massive “clover-leaf” freeway interchanges starting to appear in Hollywood television and film presentations.

In December, 1955, an Order was gazetted approving the making of “the new Heidelberg-road” in the City of Collingwood, “funds being legally available for acquiring additional lands”. The ramps were subsequently added to the definition of the main road in December, 1957.

(Below) The Preston-Reservoir railway bridge over Queen’s Parade circa 1930 with cable tram and the Terminus Hotel just visible right. The roadway was lowered around 12 feet in 1940 to allow for double-decker buses. :

(Public Record Office of Victoria Item ADV 1093) Feature image above ADV 0905)

Hi Brian,

I see your name coming up quite a bit with the research you do from time to time. I have recently moved back to Melbourne from WA (grandkids) and my interest is military history. Now the Memorabilia and Research Officer for the Glenroy RSL.

My Great Grandfather was Hon James Membrey and his daughter Alice my Grandmother, her son Eric my father.

It would be interesting to catchup sometime if you are available for a chat.

David Kirton

Hi David,

Your comment has been passed on to Brian.

Regards Wikinorthia admin.