It was a still night; cold and dark. From the distance, the orange glow of the fire barrels could be seen. Sparks shot up and danced as high as ten metres in the air. The crowds gathered round, absorbing the radiant heat to keep out the chill.

It was a still night; cold and dark. From the distance, the orange glow of the fire barrels could be seen. Sparks shot up and danced as high as ten metres in the air. The crowds gathered round, absorbing the radiant heat to keep out the chill.

A voice over the loudspeaker attracted attention. The masses moved reluctantly from the warmth, across the road to the memorial. It was impossible to tell how many.

There was silence as the Catafalque party marched along their path. Their steps so measured that they sounded as only one pair of boots treading the ground. Instructions at a whisper carried across the still air. They took their places at the four corners, turned outwards, rested their guns and bowed their heads in silent mourning.

A single shot broke through the trees, and then another, to be replaced by several short bursts of machine gun fire. The light from the automatic weapons gave away their position amongst the trees.

In those few seconds in the pre-dawn of April 25th it was easy to imagine how many unsuspecting soldiers were cut down on the shores of Gallipoli before they knew what had happened. The Anzac Service at the Simpson Barracks had begun… and we remember.

When we stand in silence and remember the sacrifices of past wars, I think of Henry. I knew nothing of Henry until my grandmother died several years ago. Her belongings were a goldmine of information – among them were Henry’s records.

A local lad, born and bred in Eltham, Henry [Norman] went off to war in 1915 and never returned.

Twenty-two years of age, five foot 4 ¾ inches tall, 10 ½ stone. Dark brown hair, brown eyes, fresh complexion; his enrolment details were accurate down to the vaccination mark on his left arm and a scar on his left shin. Accurate enough that I can visualise this handsome young man.

Enlisting in June, he found himself in Gallipoli by the end of August. He was there until the evacuation.

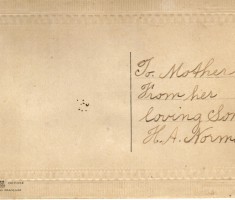

March 1916 found him in France, where he made and sent home a present for Mother’s Day. “From Her Loving Son” the hand-embroidered card is signed. He had the most beautiful handwriting, indicating a time when such things were important.

By August 5th, he was dead. The official letter from the War Office was addressed to his father only – mothers having no significance in those days. A report from his commanding officer, and a witness who was with him. They were in the front trench at Pozieres when the battalion was relieved and encountered heavy shelling on the way to “Sausage Gully” where they were to spend the night. Two hours later when the battalion regrouped, Henry was gone.

Can a father find solace in the words of praise written on paper? Does the cold metal of a service medal replace the warm flesh and blood of a mother’s only son? Do young girls not mourn their brother?

I knew one of Henry’s sisters. She was my great grandmother, and I can’t begin to imagine how she felt when her only son, also named Henry, went off to war in 1940. Luckily, he returned.

Henry is not the only relative I have lost, but he is the one I know most about. He is as real to me now as anyone I know.

As the dark becomes light and the fog begins to lift, a bugler plays “The Last Post”, the soldiers stand in silent vigil, and we bow our heads in a minute’s silence, I think of Henry. And all the other Henrys.

Story: J. Meekins

This story was first published in “Fine Spirit and Pluck: World War One Stories from Banyule, Nillumbik and Whittlesea” published by Yarra Plenty Regional Library, August 2016

2021. Henry Albert Norman (service no 1814) was in the 22nd Battation and died on 5 August 1916. He was born in Research, Victoria (near Eltham) to Robert and Harriet Norman.